Contents

- Leaving my home in NYC

- Arriving in Bogotá: Landing in a new world

- Inside the jungle

- Lifestyle of a Colombian family

- The almighty dollar

Leaving my home in NYC

“Woohoo!!! Freedom! Ultimate freedom!” I shouted over and over again like an idiot as I walked out of the Bloomberg LP headquarters in Midtown Manhattan. The day had finally arrived, the day I quit my brutal job in finance that I’d held for the last 5 years to travel the world and spend time reading all the classics and sipping on virgin piña coladas. It was one of those times in life when I couldn’t care less what a stranger on the corner or at the bus stop thought of me, because for the first time in my life, I was on an adventure that was completely on my own terms. I was my own boss, for once in my life. I didn’t have a job or school, or any responsibilities. I was a single, 26-year-old man who was as free as a free can be, with the whole world to gain and nothing to lose.

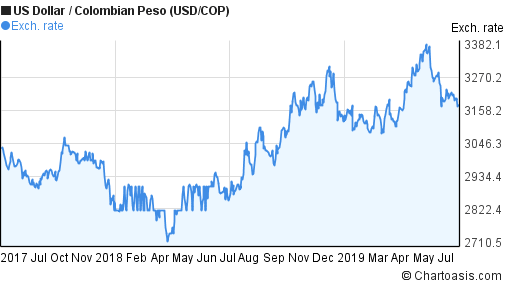

I booked my flight on April 1st, the same day as my official last day of work at the office, and everyone made a point to mention how this had to be some big joke for April Fools Day. I didn’t waste any time because I was already sure what I wanted: a new environment that would challenge me to grow in ways that were totally foreign to the lifestyle I had grown accustomed to in New York City. I wanted to know what it would be like to set foot on alien territory, to embrace a language and a habitat that were not my own, and see if I could put together the basic elements of a happy life: friendship, community, a sense of purpose and meaning, enjoyable work that would give me a feeling of importance and dignity, and, who knows, perhaps a lovely Colombian señorita. I had good reason to suspect that achieving these goals would be possible. I had social connections in Colombia already through friends in Catholic youth groups I met in New York, one of whom had arranged for me to stay with his family in Bogotá my first month in April 2019. Surely, I thought, I would have people with similar likes and interests to hang out with. I also spoke fluent Spanish, though I was a bit rusty after having gone 5 years without practice since I graduated from college in 2014. Better yet, I had also heard the exchange rate was excellent at the time between Colombian Pesos and the American dollar, with one dollar being worth 3,200 Colombian Pesos. On a normal American salary you could live like a king in Colombia, and after 5 years of working as a software developer for the largest financial services software company in the world, I was more than ready for that lifestyle.

Before I left I had a very nice going away party with some Church friends in New York City. Over the last 2 years, this group of guys had become my best friends, the people I would spend late nights with debating philosophy, theology, and morality, the people I would proudly stand next to volunteering with in soup kitchens on Sunday mornings, the people I prayed with in quiet times of reflection and on spiritual retreats, and the people I drank and laughed with at too many special occasions to count. I loved how we were all so different yet so similar. We had different ethnic backgrounds, different home environments we were raised in, and different career paths, but we were all highly intelligent and committed to seeking the truth and the fundamental nature of reality, and to using our talents and gifts to give something back to the world, even if only in very small and simple ways. Here’s a picture of some of us at our last hangout before I made the plunge:

More pictures and videos of that going away party can be found here: https://photos.app.goo.gl/RrVpezTeCDmmDqmQ9

Arriving in Bogotá: Landing in a new world

I landed in Bogotá, Colombia in the afternoon on April 2nd, and I took in all the scenery like a baby who was just seeing a television set for the first time. When I got on the connecting flight to Bogotá that left from Fort Lauderdale, all the flight instructions were in Spanish, and I found myself sitting next to a Colombian and joking about how we could get great seats for free because there were several empty window seats. In a flash, I was in a new culture, in a new world, even if I was just dipping my toes at the shallow end of the pool.

In a few hours I was knee-deep in the new world. This is what the immigration line looked like at El Dorado airport in Bogotá:

I sent this image to my friend’s dad to explain why I was taking so long. In the end he ended up waiting over 2 hours for me outside as I went through immigration.

Finding my friend’s dad, Fernando—the host of the home I was staying in

—proved to be a challenge. He didn’t speak a word of English and his accent took some getting used to. I had to ask for clarifications several times on the phone but we eventually made it happen. We had a cordial embrace when we finally found each other and then he told me he would show me through the jungle as we went on our way home on the bus.

Inside the jungle

The transit system in Bogotá can feel like a zoo to a foreigner. All the buses have different letters and numbers and go to different routes on several different lines. The system is known as Transmilenio and if you’re going to survive the city in Bogotá you had better know how to use it. Getting on felt like boarding the subway in New York City: you brush up real close to strangers that in any other situation you wouldn’t touch with a 10-foot pole. One difference was the element of danger which was a lot more palpable than what you feel on the subway in New York. On Transmilenio it’s well known that people will try to swipe your phone and run sometimes if you leave it in a vulnerable position like the back of your pocket. Fernando advised me well to keep my phone on the inside of my jacket and to be careful with my belongings. He told me that in Colombia it’s important to not “dar papaya” which is a Colombian slang term for putting yourself in a position to get taken advantage of or robbed. I wasn’t afraid though, but more excited at the challenge of adapting to the new environment. I also noticed that as we talked on the long ride home I got used to his accent more and more and we could converse comfortably.

Lifestyle of a Colombian family

All families everywhere across the world are different, but there are some distinctive elements that you notice when you travel to different regions. In Colombia, the big things that stick out are hospitality, resourcefulness, and a love of the natural fruit of the earth. The hospitality and warm welcome I received from the moment I stepped in the door took me by surprise like a beautiful sunset that suddenly emerges on a cloudy day. I thought I had come to Colombia as just a friend staying with a friend’s family but they treated me like I was someone who was especially important: my bed was always made for me before I went to sleep, my private bathroom was cleaned regularly, and they cooked meals for me taking into account all the idiosyncrasies of my taste buds. They had two extra rooms since their son Juan (my friend) and daughter Laura had been in the United States for years. They were happy to receive the $150 monthly rent I was paying them which was about a tenth of what I paid for rent in New York for a much worse overall living situation. We also shared lively conversations at every meal about what was going on in the city, or about politics (Fernando is really big on politics, don’t get him started on all that is wrong with the world), or about Juan’s friends in the city that I should connect with. I have a couple of pictures inside their apartment:

The hospitality I received in Colombian households didn’t exist in a vacuum, but rather the greater Colombian culture of warmth and friendliness. Whereas in the United States people give a perfunctory shake of the hand when they meet for the first time or greet each other, in Colombia greeting was a more elaborate ordeal. With men there was often a touch on the upper arm or shoulder, as if to say you weren’t a stranger, but rather a long-lost relative that is being welcomed back into the family. With women, there was always a kiss on the cheek and an embrace, even if it lasted only a brief moment. The gesture conveyed a warmth and passion that I rarely, if ever, felt when meeting new people in New York City.

After the hospitality, the next major thing that struck me while living with a Colombian family was a love of the natural fruit and food of the earth. Colombians love their regional juices, and when I say love, I mean LOVE them. Every few days we tried to have a different juice. We had “jugo de tomate de árbol” (tree tomato juice), which was one of my favorites, we had lulo juice, we had maracuyá juice, we had guanabana juice, and more that I don’t even remember. Each fruit juice tasted both exotic and a bit acidic, like a fruit punch with a bit of an extra kick in it. I had no idea that natural juices could be so delicious. I once stopped in the kitchen to watch Fernando preparing a juice for me and was shocked that all he did was squeeze the fruit and pour it into a glass. I thought for sure he was adding a number of things to it to make it fizz a certain way or have that extra bite in the taste, but that’s just how the fruit actually tastes. Here’s a picture of myself and some friends getting lulo juice in the city center in Bogotá (lulo was one of my favorite juices):

Another quality that really struck me was the resourcefulness of Colombian households. When articles of clothing needed to be dried, you’d find them hanging on the balcony and on door handles, where they could drink sunlight like running water. When the tv or remote control wasn’t working, the solution was not to take it to a repair shop, but to look up youtube videos and follow the steps carefully on every single one until you finally struck gold. When you got sick, you don’t stock up on NyQuil and cough drops, but you pop a few pills of acetaminofén (Colombian version of advil), wash it down with water and some chewable vitamin C, get some rest, and see if that works first. Any kind of waste, no matter how small, was more than an oversight in that household, it was a mortal sin.

Aside from sharing in the delights of Colombian family life and social interactions, I also experienced the sobering realities of the underside of family life that is universal across cultures, time, and geography. In every family I spent time with there were secrets, there was some form of discord, whether openly expressed or muted, there was someone who felt that they were always at the losing end of compromises, and there was always some form of dysfunction, whether only at a small scale or a scale that permeated every interaction. There was always a generational divide between parents and their young adult children, and between those same parents and their children’s grandparents. The closer a look I got to some of these situations, the more I became horrified by the intractable nature of so many of the problems. A lot of times it was nobody’s fault, it was just the way the cards were dealt—a group of people had been placed together through an almost forgotten commitment made long ago coupled with the accidents of biology, and the result was a smorgasbord of personalities, viewpoints, and convictions that did not form a harmonious melting pot, but rather a grotesque mosaic.

The almighty dollar

As a Western Expat, one of the first things you notice when you set about living life in Colombia is how cheap everything is. I don’t think anyone can really appreciate the term “privilege” until they come face to face with its opposite. I remember the first time Fernando took me out to get a haircut and was horrified when I tipped the barber 6,000 Colombian Pesos for a 16,000 Colombian Pesos haircut. The way I was thinking about it was “Wow, it used to cost me $40 in the United States to get a good haircut and on top of that I would leave a $5 tip. I just showed this Colombian barber a picture of how my hair should be cut and he did a great job. Since 10% of the haircut is only 1,600 Colombian Pesos or $0.50, the least I could do is give this guy the equivalent of $2.00 or 6,000 Colombian Pesos.” Fernando told me that my behavior was a classic rookie-mistake and that engaging in that kind of behavior just causes local businesses to raise prices and it puts you personally in a position to get taken advantage of as a foreigner. Tipping more than 10% isn’t necessary, even if the equivalent in your home currency is pennies.

Housing was similarly inexpensive. I had just spent the last 4 years in Queens, New York where I paid $1,375 a month for a studio apartment by the time I left in 2019. In Bogotá, I lived with Fernando and Marta (his wife, Juan’s mom) for 500,000 Colombian Pesos, equivalent to $150 a month which included a private room, a private bathroom, both of them cooking for me, a doorman, and an overall better, more enjoyable, living situation than I had in New York for about a tenth of the price. Leaving a high-paying job in the finance industry will give anyone doubts about whether they made the right decision, but after my first week settling in, I didn’t have any doubts that a year-long sabbatical was just what the doctor ordered. Little did I know, the journey would get even more exciting in the coming weeks…

I’m extremely impressed with your writing skills as smartly

as with the structure for your blog. Is this a paid subject or did you modify it yourself?

Anyway stay up the nice high quality writing, it is uncommon to look

a nice blog like this one nowadays..

Thanks Royal CBD! This is not paid, I do this because writing and sharing my life experiences is one of my passions. I’m happy to hear you found the writing valuable and would love and appreciate any feedback. Cheers!

Hello! I’m at work browsing your blog from my new iphone!

Just wanted to say I love reading through your blog and look forward to all your posts!

Carry on the excellent work!

Does your site have a contact page? I’m having trouble locating it but, I’d like to send you an email.

I’ve got some creative ideas for your blog you might be interested in hearing.

Either way, great website and I look forward to seeing it expand over time.

It does not have one yet, but you can reach me by email at thorpep138@aol.com